Vladimir: “We are not saints, but we have kept our appointment.”

Almost five years after his death, my daughter and I made the pilgrimage to place her father’s ashes in his family crypt in Brooklyn. Tony, like so many men before him, had been an indifferent father. Though not as ‘important’ as his own father, Tony had been far too important to be concerned with the childhood of his children. While ‘distant’ as a father, it must be added that he was a pretty awful husband. With such a dark--but not especially unusual for its time--family history, it is essential that I go on to address Tony’s Redemption. His redemption, like a rich and nourishing meal clumsily served at The Last Stop Café. Tony spent his final years making amends, stretching his elderly limbs over the chasm of his past as father and husband.

Some of the story

Tony & I had our first date on December 9, 1965. We were married four months later.

The following spring, Tony and most of his colleagues resigned in protest after the administration at Tulane University refused to commit to building a theatre for their internationally-known theatre department. Tony’s colleagues went on to head theatre departments at such places as NYU, Illinois State, and Temple University. Tony came to Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State Institute to establish a theatre department, a unique opportunity to begin at the beginning. Our first born, Paul, was seven months, and I was twenty one years old when we moved to Blacksburg—then, a town of 7,000. Our daughter, Gretchen, was born the year Tony directed Measure For Measure and our youngest son, Tod, the year of A Funny Thing Happened on The Way To The Forum.

Tony worked days and nights and weekends, expanding the department, promoting the arts at a former military and agricultural college; back then, a most fallow field for the arts, a Quixotical task if ever there was one. He helped form the Virginia Theatre Association, became President of the American Theatre Association and Dean of The College of Fellows of the American Theatre. He put the young Theatre Arts department into a national spotlight. Tony turned down a deanship at Penn state and formed the Marching Virginians at what, by then, was beginning to be called “Virginia Tech.” Tony led and chaired the growth of a department of music. The combined departments merged to form the School of The Arts, with Tony as director. In those intense, hardworking, tireless years completely devoted to the university and his profession, our household went on without him. Tony worked harder. He envisioned a future where, one day, there might actually be a formidable performing arts center on campus, his lance pointed at windmills. In those intense, hardworking, tireless years completely devoted to Virginia Tech and his profession, he missed birthdays, family dinners, ballgames, plays, and teacher conferences. His young family slipped away. In November of 1978 the children and I left the drafty 200 year old house on Shadow Lake Road for a tiny house in downtown Blacksburg.

“Discipline is the essential ingredient of art,” Tony told his students. He worked ever harder, spreading the word of the power of art to transform.

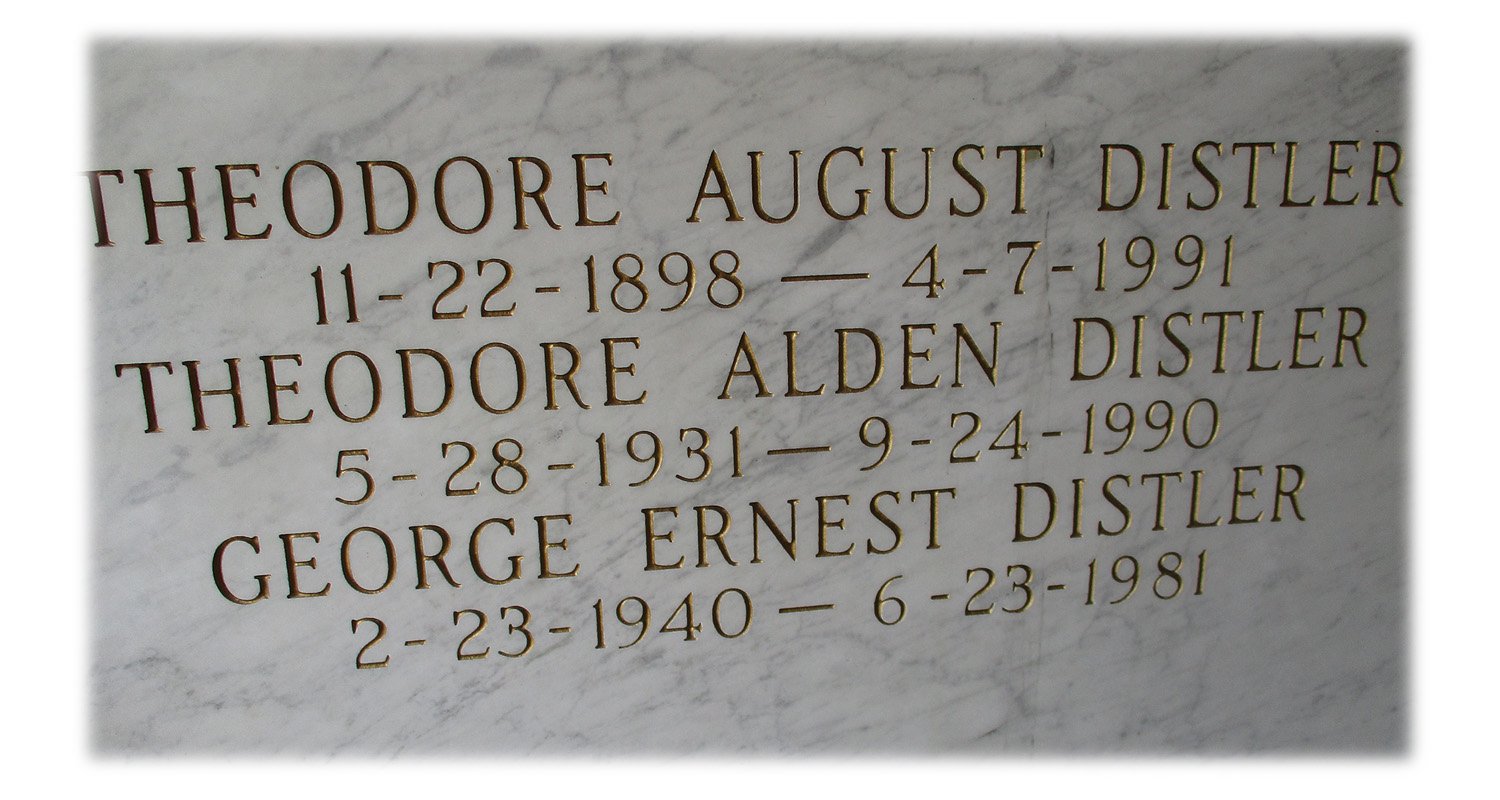

His work drive took his family and his drinking kept Tony from the life he deserved. His youngest brother died in 1981, his oldest brother in 1990. He was alone in that 12 room house on Shadow Lake Rd for almost 40 years. It was probably not until after he left the University and navigated the waters of institutional amnesia that he realized what he had given up, what he had missed: the first steps, the birthdays, the bedtimes, the bad dreams and funny dreams, the first loves and last school days of his beautiful three children; the buzzing, growing, stretching of the community his family had created. Tony woke up to the missed years and his missed chances.

He paced the waiting room while his first grandchild was being born and became a wildly devoted grandfather to her and to the ensuing other four grandchildren. Tony gave his time and money; sleepless nights of worry, and summer seaside afternoons of delight to his family—the three children who had been there all along and the five, precious, unique, off springs of the three.

While he was parsimonious with himself—Tony’s lunches were baloney sandwiches, he drank generic vodka and bought all of his clothes at Penny’s--his generosity to his children and grandchildren was boundless, as was his philanthropy to the schools he attended and to The Lyric Theatre, The Warm Hearth Foundation, and Planned Parenthood.

It is true that Tony did not have the personal life we would have wanted for him; but he appreciated the life he had. He gave almost everyone the benefit of the doubt. And he always, always loved to milk a joke. He died, surrounded by his loving family, in that big old house on Shadow Lake Road. A lifelong member of Actor’s Equity, he was a consummate show man who continued to look forward to each new season. Tony Distler reluctantly left the stage just as the curtain was closing on 2016. Art and Redemption were the show of his life.

My sons--for different reasons, but reasons all their own—chose not to join Gretchen and me in taking their father to be interred with his own father, mother, and siblings. So, it was just the two of us catching the train from Roanoke to Penn Station on an early morning in June. It had been planned that we would meet Tony’s sister-in-law and her oldest daughter in New York, but they were forced to cancel two days earlier. Gretchen and I would be the only mourners at the cemetery in Brooklyn. We carried Tony’s ashes in a beautiful urn, bundled in bubble wrap, tucked into Gretchen’s suitcase, and stored in the overhead rack. Slipping our masks on and off, we nibbled on snacks, drank wine, and read during the 8 hour train ride. A lovely easy day, summer scenery passing by.

New York had only just ‘opened’ from its Covid shut down the week before. The night we arrived in Manhattan, we dined in our hotel’s spectacular restaurant and it was crowded with beautiful people wearing clothes we’d only seen in glossy fashion magazines. The Beekman hotel was lovely and secluded; walking distance from the Brooklyn Bridge, and crazy expensive.

We spent the next morning meandering the High Line and browsing through the Whitney, where—because of Covid restrictions--we were part of a sparse and socially distanced group. It was a privilege. We had an early afternoon reservation for the opening of the Distler Family crypt. So, we caught an Uber from SoHo to pick Tony up at the Beekman and take him to Brooklyn where his parents and siblings were waiting.

We settled into the back seat of the car; Gretchen cradling the urn of ashes in her lap; me with a small cooler in mine as we rode over the Brooklyn Bridge into clusters of leafy neighborhoods and past a scattering of sun blasted shopping centers. My daughter and I were quiet during the long drive, each of us drifting in very different memories of her father. As he aged, and she matured, Gretchen tended to Tony more and more. In mid-autumn of 2016, he was diagnosed with terminal cancer and died three days after Christmas. Gretchen took a leave from teaching to look after him as he was dying. She kept company with her father in the house where she had lived for the first nine years of her life. Almost five years after his death she was still deeply mourning Tony. He had been my husband for slightly over twelve years. Those twelve years had long been put to rest, and I know I was thinking only of the redeemed Tony, and, among those thoughts, a particular memory:

The scenery began gradually to change until we were driving through neighborhoods of abandoned buildings, trash-laden streets; store fronts and open car windows blaring dueling music over the scream of sirens. It seemed the further we were from Manhattan, the more desperate and rundown our surroundings. Gretchen and I found ourselves dreading our destination, fearing for where the end of Tony’s road might be. Then. . . and then, the driver turned off a noisy, crowded intersection and drove through high stone gates into a lush green place of gardens and ancient trees. ‘An oasis Grows In Brooklyn.’ It was as though a door had subtly closed behind our Uber. We were enclosed in a place of enchantment. The car left everything urban behind and we were now gliding into a silent and shimmery June; a forest opening filled with lovely marble cottages, family crypts. Tony’s last stop was in the Evergreens Cemetery, a unique place founded in 1849 as the first secular cemetery in New York. The marble crypts bore writings in Hebrew and Arabic, French and German; some of the crypts were like small palaces, others were humble stone huts.

We had hosted a full weekend memorial in Virginia the May after Tony died—all of his family present, and his most beloved former students, eating, drinking, telling stories—lots of laughter. But this June day, in the shadow of the Distler crypt, was elegantly personal.

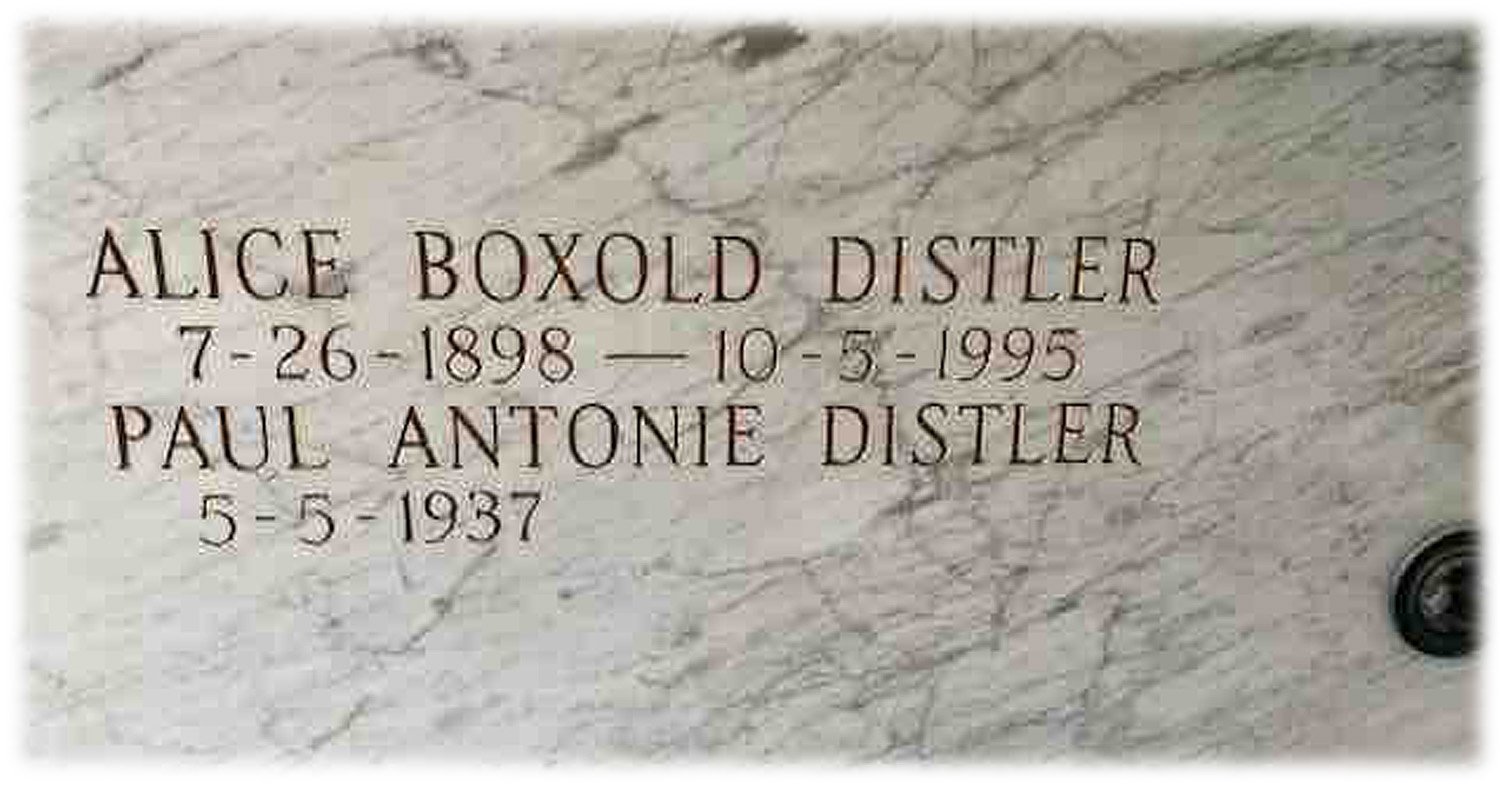

We stood in the cool darkness and read the names of family we had known and family who were only legend. We toasted Tony with the small bottle of champagne I managed to keep fairly chilled.

Gretchen had expected to weep and instead found herself laughing at the stories of the 4 brothers from Queens who had opened the crypt for us, respectively left, and then returned to seal Tony into his rightful place. They were like the comic relief in Hamlet. Those good men were enamored with Gretchen and vied for her attention, trying to top one another in Tales From The Crypts: ‘the biggest crypt,’ ‘the most haunted,’ ‘most eccentric’. All of which made the end of Tony’s journey much less grave. He would have loved it.

PAUL ANTONIE DISTLER

Born May 5, 1937; died December 28, 2016

Father of Paul Conrad, Gretchen Elizabeth & Theodore Eliot

“Good night, sweet prince, may flights of angels sing thee to thy rest.”